The day of my university graduation was also the day I learned that I had a place on a PGCE course. My other half, who did not know my parents very well, sat down with them for a coffee while I got my robes fitted.

“Are you ready?” – My mother, a teacher who at that point

had around 35 years of teaching under her belt.

“…For what?” – My other half

“This is going to be the hardest two years of Becky’s life.

You’re going to need to support her and you’re not going to see much of her

until she’s at least out of her NQT.”

When I met up with my cheering session after the ceremony,

he looked paler than I did.

It’s now been eight years since that fateful conversation

and my other half has more than stepped up to the challenge; he’s cooked

dinners, ironed shirts, cut out lettering, dropped off forgotten books, made

banana bread for the team, prepared an ungodly amount of chicken for ‘Humanities

Fajitas’, and he can even tell you what TLAC stands for. Most importantly, he

has always graciously accepted that I’m unavailable on weekday evenings and

that Sundays are my ‘work day’. However, over the last two years, I’ve begun to

claw some time back for myself, for him, and for my team without sacrificing on

quality. I’ll admit, the Mr. signed up for two years of intense support, rather

than eight. However, I feel that the changes we have made within our team mean

that this time is here to stay, rather than just robbing Peter to pay Paul.

The main change we introduced was centralised resources.

To me, centralised resources do not mean one-size-fits-all,

off the peg, could just buy it off the TES generic Powerpoint presentations.

They mean fully resourced ‘base lessons’ (usually with reading texts) in which

the threshold concepts have been clearly signposted. Staff are responsible for

individual units which they plan well in advance and into which they can sink significant

amounts of time and love. The staff which then use these lessons know exactly what

they need to focus on, but they also have the flexibility to adjust for their

individual groups.

Why do I believe in centralised resources?

I believe that 99.9999% of teachers want the very best for

their pupils and are willing to commit significant time to ensuring their

pupils succeed. I’m also willing to bet that the same percentage of teachers do

not want to spend every second of their waking lives outside school planning and

marking. The problem is time. When teachers don’t have enough time and don’t

have a strong system of centralised resources, they end up in a vicious cycle

of ‘survival planning’ which bleeds them dry of any time or will for development:

The reason why this cycle is so harmful is because it is so

difficult to break. Without significant intervention, it can slowly wear

teachers down year after year, making them feel that every September they are

starting from scratch or causing them to reuse resources which they know are

not fit for purpose as they do no feel that improvement is possible or

feasible.

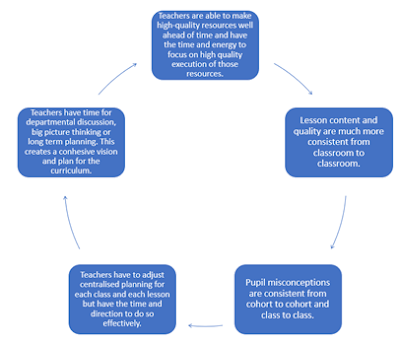

However, when this cycle is broken and high-quality centralised

resources become the norm, a virtuous cycle can be created in which staff have

the time and the desire to continually improve their resources and teaching

without feeling overwhelmed.

Why did we resist centralised resources?

I think there are a multitude or resources why teachers can resist

centralised resources:

1.

Time: although centralised resources aim to

reduce the amount of time spent planning or creating resources, starting the virtuous

cycle above requires a significant input of time from one person or every

member of the team. This initial push can seem impossible to start.

2.

Working = making: certainly when I started

teaching, I felt as though work needed to be physically productive; if I was

working, there had to be something to show for it. I usually felt that that ‘something’

had to be a resource. Therefore, to use someone else’s resources was somehow

cheating or stealing.

3.

Personalisation: once again, at the beginning of

my career, the educational zeitgeist seemed to heavily push the idea that every

pupil was entirely different and therefore every lesson had to be entirely

different. Resources could not be reused between classes or cohorts as they

simply would not work.

4.

Ego: linked to the idea of ‘cheating’, part of

me initially felt that centralised resources were somehow a comment about the

quality of my planning; needing to use these resources apparently clearly

demonstrated that my planning wasn’t good enough.

Many of these reasons focus on self-perception, potentially turning the introduction of centralised resources into a minefield. As a result, I believe they need to be implemented gradually and carefully.

How did we introduce centralised resources?

When introducing centralised resources to a team, I believe

it should be done in a phased approach in order kickstart the virtuous cycle

without making staff feel overwhelmed and to ensure that staff are bought-in to

the process in the long term.

Stage 1: ‘The One Man Model’

The concept of centralised resources is sold to the team in

person. Emphasis is placed on the virtuous cycle (as the long-term goal) and

the short-term gains of reduced workload. One or two members of staff (probably

department leadership) lead on producing resources, possibly only focusing on

one or two units. The staff producing resources clearly signpost threshold

concepts. At this point, emphasis should be placed on staff simply using the

resources, rather than adapting them.

Ideally, a faculty/department meeting should be spent evaluating

the centralised resources which have been used. This is a good opportunity to kick

start a collaborative approach and a to dispel any myths that centralised resources

are a critique of other teachers’ resources.

Stage 2: Adapting individual lessons

Once staff are in the habit of using centralised resources

and can see their benefit in terms of workload, leadership should lead training

on how to adapt resources for individual classes. Adaptation should have a ‘tight

but loose’ approach which encourages staff to be responsive while also focusing

on threshold concepts. Members of the team could share and discuss their

practice in line management meetings and faculty meetings.

Stage 3: Delegating units

Planning starts to be shared out beyond leadership, well

before they need to be taught. Line management meetings should include discussions

about progress with planning and should serve as an opportunity to check

through and discuss resources.

Stage 4: Collaborative evaluation and planning

Checking, evaluating, and planning become a process in which

the entire team is involved. All members of the team have planning

responsibility and units are reviewed, evaluated, and tweaked as soon as they

have been taught. Teachers of different units regularly discuss with each other

in order to gain feedback and to see where they can build on previous units. The

team develop threads of schema and second order concepts which allow for

effective interleaving, interweaving, and mastery.

Comments

Post a Comment